Here are a few thoughts about one of the most useful tools we have, to give the impression of depth in a photograph. It is reproduced from my Blog, and I hope it clarifies the use and meaning of perspective effects in a photograph.

Previous cultures understood pictorial perspective, but in its mathematical form, linear perspective is generally believed to have been devised about 1415 by the architect Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446) and codified in writing by the architect and writer Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472), in 1435 (De pictura [On Painting]).

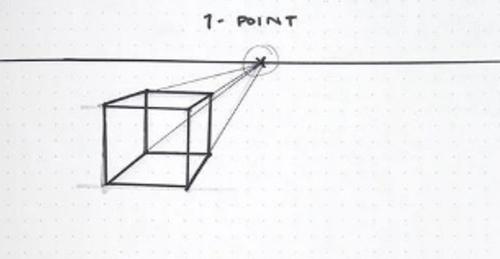

But, Brunelleschi, Alberti, and others only understood one point perspective, the simplest pictorial form of perspective. We have just one point where the sightlines converge. Central perspective, however, is so violent and intricate a deformation of the normal shape of things that it came about only as the result of prolonged exploration and in response to very particular cultural needs. Curiously, the distortions imposed by perspective on the real, tactile world are so successful that modern viewers only note them when pointed out.

If we construct a perspective drawing, or use perspective in a photograph, the angle of view is a question of proportion, that can be explained by tracing an image on a window whilst looking through a small hole at a fixed distance. A simple illustration explains the concept nicely. It is obvious that the angle of view and the steepness of the sightlines are infinitely variable.

Quoting a pamphlet on the use of perspective in Renaissance painting, published by the British National Gallery, we can understand that sometimes we need to depart from pure geometric, or mathematical models:

“Optical illusion does not necessarily depend on mathematical absolutes and, with a few important exceptions such as Piero della Francesca, it seems that painters were more concerned with achieving a level of visual plausibility than with the rigorous application of theoretical models. Perspective was designed to fulfil the needs of the picture (not vice versa), and a series of other conditions and criteria were at stake: the knowledge, skill and aesthetic preferences of the artist, the demands of patrons, the ways in which the site might determine the viewpoint, and the requirements of the subject matter. Thus, a painting which has often been considered a perspectival manifesto, Masaccio’s ‘Trinity’ fresco, has been shown to bend the rules of one-point mathematical perspective, probably because it looked better that way”

Construction of a One-Point perspective drawing

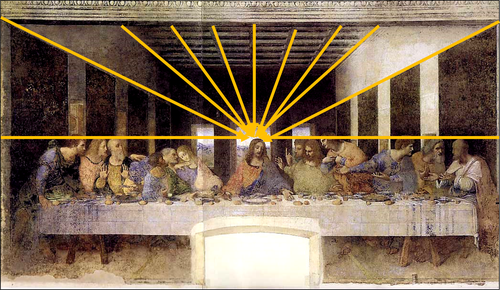

Sight lines for Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper

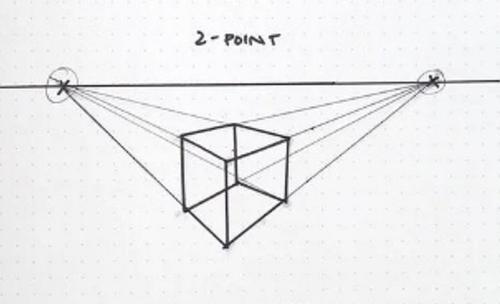

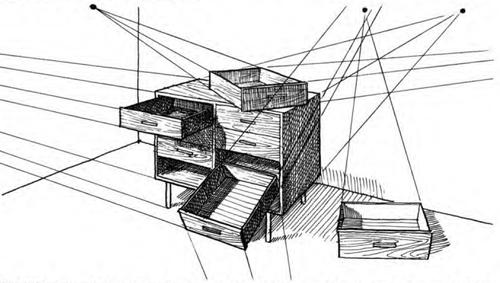

Two-point perspective, necessary to show objects set at an oblique angle to the viewer, took another century to evolve. The first known diagram of the two-point perspective by Jean Pélérin, in his De Artificiali perspectiva (1505), which was also the first printed treatise on perspective. With two-point perspective, there are two vanishing points on the horizon line. This creates the illusion of depth and space

Two-point perspective is probably a much more useful, than one point perspective, if we want to create an illusion of a three-dimensional object in a photograph. But it is harder to control and unwanted perspective effects can creep in to make a picture look unnatural.

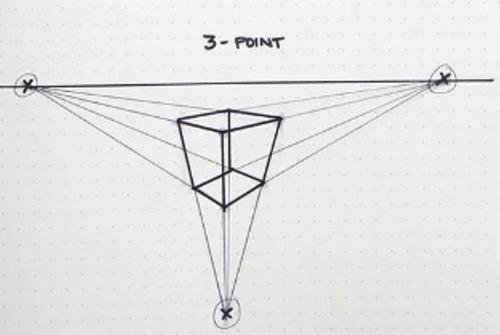

Three-point perspective is a type of perspective that uses three vanishing points. It is used to draw objects that are above or below the viewer’s eye level, such as skyscrapers or bridges. In three-point perspective, the lines that are parallel to each other in the real world converge to three different points on the horizon line. Three-point perspective is closely connected to two-point perspective, and is generally unwelcome in Architectural photography. Three-point perspective often appears as “key stoning” in a photograph.

Let's look at some real world examples. With Aldo Rossi's Ossario in Modena as an example. I made three pictures with one, two and three point perspective.

When we look at a reasonably low building like the one above, our brain applies key stone correction, and we see the vertical walls as being vertical.

A shift lens can help us produce pictures with one or two point perspective. It allows us to shift our eyesight convergence point in any direction.

Upward shift moves the single convergence point upwards

But we can also shift the convergence point both upwards and sideways, to keep the horizontal and vertical line s parallel, and create un unusual perspective effect